A joyful classroom is one in which:

● Learning is active. The students spend most of this lesson “doing”—thinking, exploring, and applying what they learned—rather than watching or listening. And that’s how they learn best (and enjoy learning most).

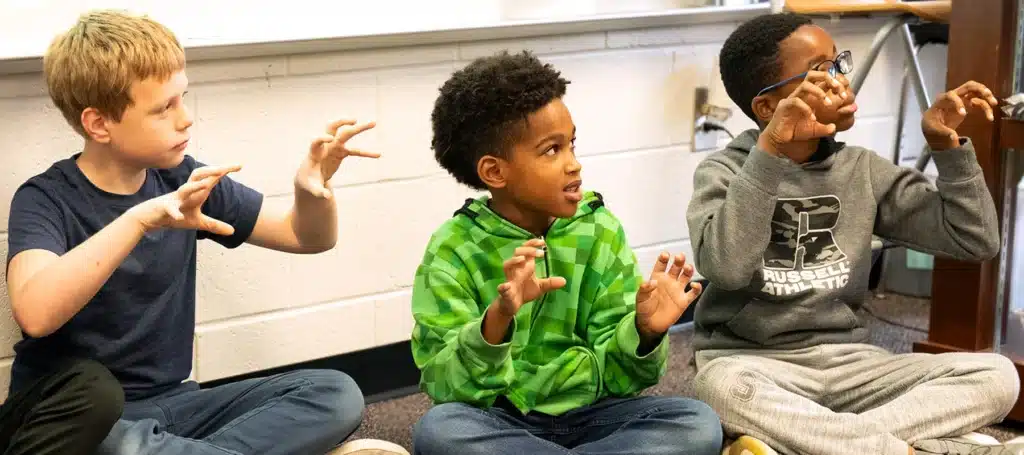

● Learning is interactive. Because humans are social beings, interacting with others enhances cognitive growth. When students work with partners or in small groups, they can talk through ideas, try things out, and hone their thinking while developing important social-emotional skills.

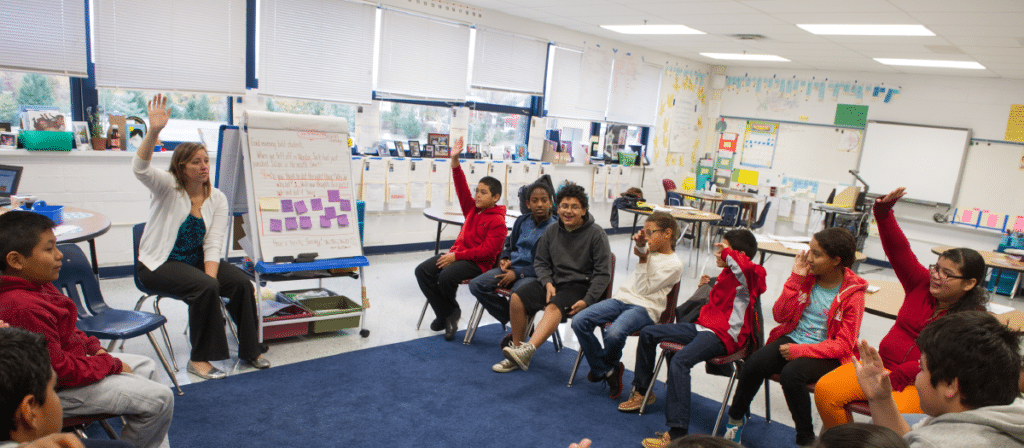

● Learning is appropriately challenging. Students can engage deeply in learning when we give them “just right” tasks—ones that build on things they already know or can do while encouraging them to reach for the next level of knowledge and skill.

● Learning is purposeful. Like adults, children are more likely to invest themselves in a task when they know why we’re asking them to do it and how it will help them accomplish something that’s meaningful to them.

● Learning is connected to students’ interests and strengths. Learning matters to children when it connects in clear ways to the things they care about most—their unique challenges and enthusiasms, communities and homes, dreams and talents.

● Learning is designed to give students some autonomy and control. Children given meaningful choices about what or how they learn become highly engaged, confident, and productive, able to persist at meeting challenges because they see themselves as capable students with a real stake in what they’re learning.

See our latest articles on creating a joyful classroom below.