Jose’s flower drawing fails to resemble what he envisioned. Ripping up his paper, he stomps away.

Abby tells Zara she can’t join a math game. Zara scowls and shoves her classmate.

Welcome to a fairly typical afternoon in my early childhood classroom, where hard-to-handle emotions can quickly bubble up and disrupt even the best-planned activities.

Just as we teachers help children recognize letters and patterns, manage their belongings, and control their movements, we must also help them identify and manage their emotions. Such self-regulation preserves social relationships and fosters fully engaged learning.

Of course, upsets are inevitable, but even very young children can learn to self-regulate when permitted to feel difficult emotions and supported in developing appropriate responses. Here’s how I teach these skills to my students.

This is always our first step. Positive time-out can be highly effective in stopping misbehavior and letting the child self-calm in a way that doesn’t feel punitive.

Feeling angry or frustrated is perfectly OK, but children often think it’s not. They may feel ashamed of and debilitated by these strong emotions. Once a child is calm, validating her emotions is key to helping her find ways to express them safely. Here are three ways to do this validation:

Share when you felt similar feelings or noticed someone else in a similar situation: “Sometimes we feel disappointed or frustrated when we can’t draw exactly what we see.” Such empathic statements help children understand and develop a story to go with their feelings. These skills help them better manage strong feelings in the future.

Young children often oversimplify, using words such as “glad,” “sad,” “bad,” or “mad” to describe their feelings. Help students build a richer vocabulary by identifying and naming a wider array of feelings. For example, once a child is calm, I might say, “I noticed you crunching up your face and pressing hard with your pencil during writing time. You looked really frustrated.”

A caution about trying to identify feelings too soon: Asking a distressed child, “How do you feel about that?” may get you only a blank stare. That blank stare indicates exactly what is going through a child’s mind at that moment: He has no idea what he is feeling or why he pinched a classmate. When pressed, he might squeak out, “I was mad!” Giving a little “wait time” for strong feelings to dissipate helps him focus on his experience and profit from your words.

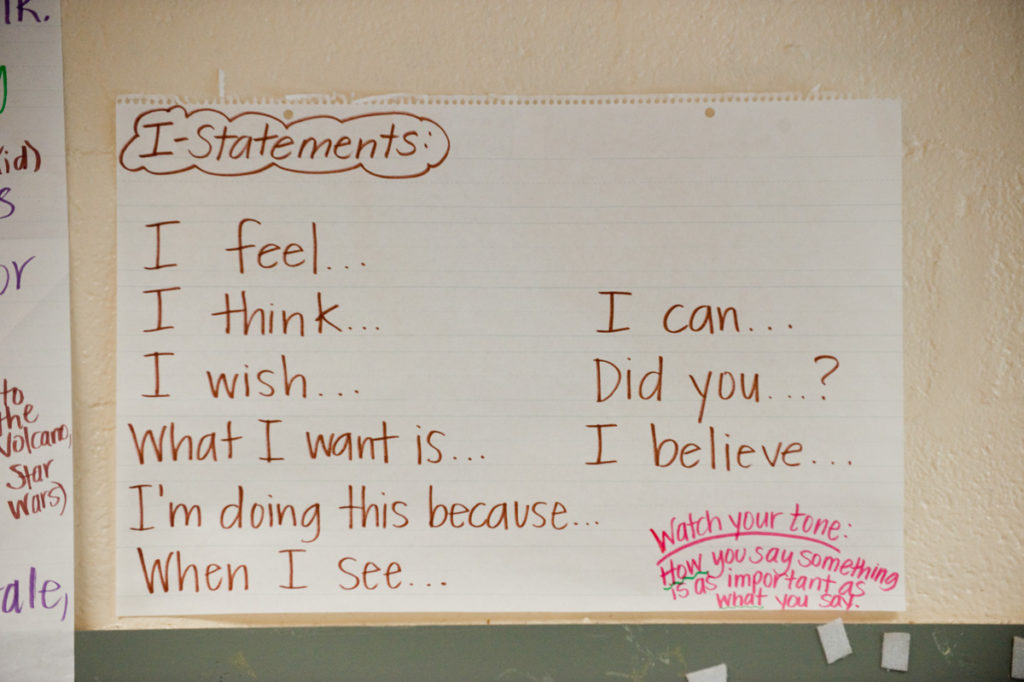

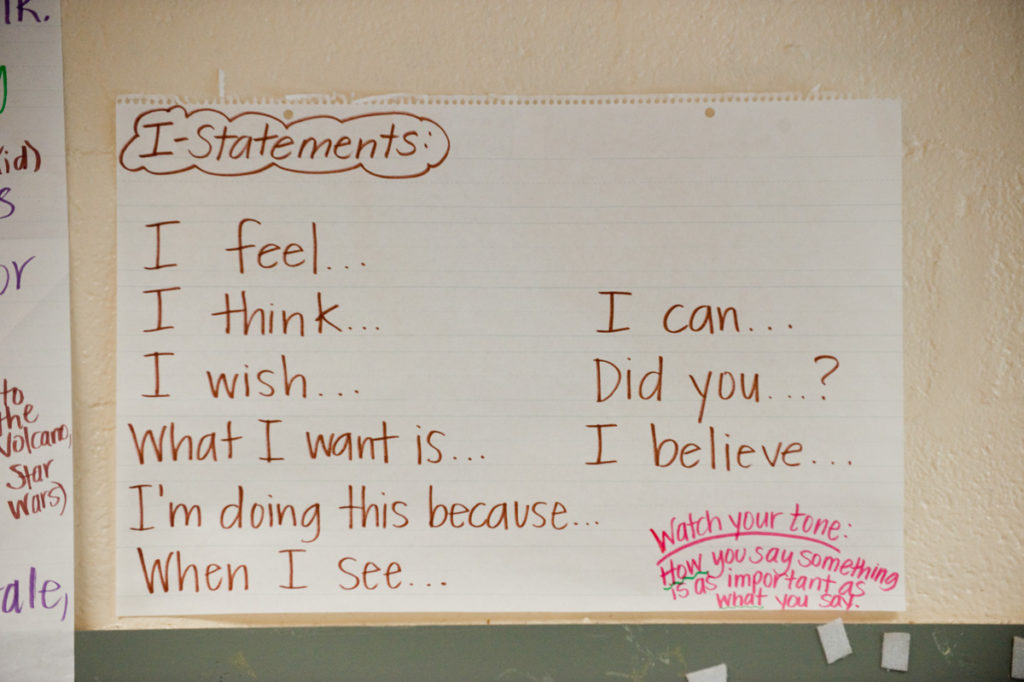

Reading picture books and identifying characters’ feelings by their body language and the book’s colors can also help build vocabulary and emotional context for identifying feelings. I frequently read aloud picture books about children who feel angry or frustrated. Recently, I asked students why they thought I shared these books. One child said, “You don’t want us to get angry with our friends.” This was an opportunity for me to explain, “No, I don’t expect you not to get angry. We all get angry sometimes. What’s important is learning how to do something to help yourself feel better when you get angry, so we can all go on learning.” Then we brainstormed and practiced choices kids can make when they begin feeling upset or losing control.

Children benefit from a quiet space in which to appropriately and safely express upset feelings through writing, drawing, song, or movement. In the art studio, a choice of malleable clay or cool and warm paint colors and various brushes encourages open-ended artwork that helps express emotions. In the pretend corner, props that encourage safe and developmentally appropriate exploration of roles and feelings let children express emotions using verbal and nonverbal language.

All children will experience disappointment, loss, and upsetting events, so the sooner they develop coping strategies, the better prepared they’ll be to bounce back and resume learning in—and outside—the classroom.

Lisa Dewey Wells is a Responsive Classroom consulting teacher. She teaches at St. Anne’s School of Ananpolis and blogs at Wonder of Children.