The Power of Morning Meeting

The earnest fourth grade girl straightened up tall and looked around the circle, drew a deep breath and began: “Our greeting today will go like this. First you say your name, then you say when you would like to have lived. Then we’ll all greet you back by saying ‘Hello’ and your name. I’ll go first so you can see how it’s done.” I noticed her hands folding and unfolding in her lap—perhaps she was a bit nervous—but her eyes sparkled.

You may recognize this scene as the beginning of a Responsive Classroom Morning Meeting, a routine that takes place in many elementary classrooms at the beginning of the school day. This Morning Meeting was different, though. For one, while Morning Meeting is typically led by a teacher, this one was led by a child. The setting and the participants at this meeting were unusual, too: it was a chilly gray April evening in Washington, D.C., and we were gathered in an enormous event room at the Ronald Reagan Building and International Trade Center. The groups gathered at banquet tables around this room included distinguished researchers, policy makers, philanthropists, and educators, some of us many times our student leader’s age. A dozen of her classmates were in the room leading similar groups.

Despite the unfamiliar setting and audience, Ellika, our student leader, was competent and comfortable in her role. The Responsive Classroom approach has been implemented for many years at her school, and Morning Meetings are a part of her everyday classroom life. She led us through the greeting, then a round-the-circle sharing of responses to the question “What’s one piece of advice you think is important for a new fifth grader to hear?” and ended with a round of “Zoom.”

We really had to focus to get “Zoom” right—passing the verbal “zoom” around our circles, making squealing-brake noises to reverse direction, ratcheting up the speed as our comfort level inched up just a bit. By the end, my awareness of the unfamiliar, cavernous room, with its chandeliers and lofty ceiling, had dropped away. Now the faces of my dining companions were what mattered. We were grinning at each other.

Somewhat remarkably, this table group of ten serious adults, most of us strangers when we sat down, had begun to feel like a fledgling community. We had spoken each other’s names, listened to and learned a bit about each other, and taken the risk of being playful, even a little silly, together.

I’d learned quite a few things about my tablemates. One wished to have lived at the turn of the century “so I could have met my grandfather.” Another wanted to see what the year 2100 would bring. One advised the new fifth grader that “effort matters.” All of us had leaned in and listened respectfully to our leader and to each other. Morning Meeting, that sturdy and simple structure, had done its work once again.

This Morning Meeting was particularly poignant for me, because as I participated I remembered Northeast Foundation for Children’s first engagement to work in Washington, D.C., more than twenty years ago. Our assignment was to introduce our way of teaching, including developmentally appropriate practices, classroom management, and community building strategies, to the early elementary grades there.

It was a pivotal time in the development of the Responsive Classroom approach; in fact, the very name “Responsive Classroom” came into use during our work there, as well as in the subtitle of the first edition of Ruth Charney’s profound book Teaching Children to Care. Now here I was, participating in a Morning Meeting led by a child who had not even been born when the first cadre of teachers led Morning Meetings in the district’s public schools. “Sometimes,” I thought, “things really do come full circle.”

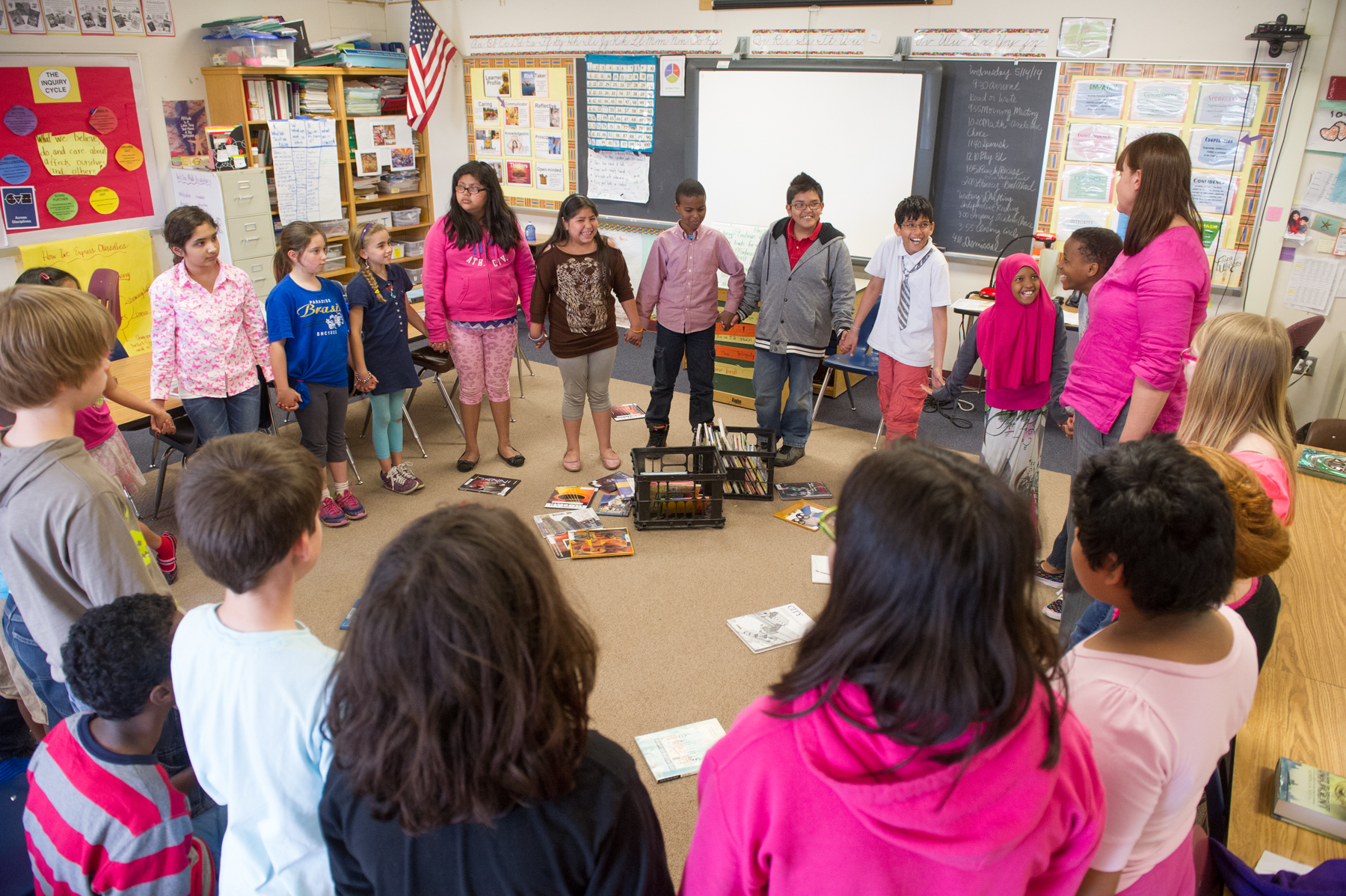

The essential elements of Responsive Classroom Morning Meeting have changed little since then. In elementary classrooms, Morning Meeting lasts approximately half an hour and takes place near the beginning of each school day. It’s made up of four sequential components and provides daily opportunities for children to practice skills such as greeting, listening and responding, speaking to a group, reading, group problem-solving, noticing, and anticipating. Teachers integrate aspects of the classroom curriculum into the routine, which helps students make the transition to school and sets a tone of interactive and engaged learning from the outset of the day.

Of course, a lot has happened in Washington, D.C., public schools in two decades. Many educational leaders have come and gone, and countless initiatives have been adopted—many of them abandoned. Yet Responsive Classroom lives on strong in many classrooms in the district’s schools, sustained and tended and taught by principals and teachers who recognize its value.

Not too long ago, an urban superintendent from Massachusetts shared a story with me that illustrates Morning Meeting’s value quite well. He spoke of visiting a school in his city one spring morning, and pausing in the doorway of a kindergarten class to watch the children and their teacher as they gathered in a circle in the corner of the room. He hadn’t intended to go in, but as he stood there, a young boy got up and headed toward him. The superintendent moved aside, thinking the boy was leaving for the bathroom, but instead the child looked up at him, extended his hand and said, “Welcome to our classroom. I’m Elias and I don’t know your name, but would you like to come to our Morning Meeting?”

This wasn’t the spontaneous act of a naturally poised child. It was the result of many days of practicing the skills of greeting in Morning Meetings and teaching each child how to welcome a visitor. “I was so impressed that this six-year-old knew how to approach a stranger in a suit peering into his classroom,” said the superintendent when he told me the story. “It wasn’t just that he had the social skills, but that he believed he had the right—even the responsibility—to look me in the eye and invite me in. That confidence and assertiveness is as important to that boy’s future opportunities as his reading and math skills. In fact, it’s what’s going to clear the way for him to get those skills and use them.”

“Morning Meeting is a silent bulldozer in the field of school reform,” proclaimed Maurice Sykes, when he was Deputy Superintendent for the District of Columbia school system. And it’s true. When Morning Meeting is a regular part of a daily routine, it clears away the obstacles that impede children from feeling safe and engaged in school, creating the space for classroom members to take care of each other and to do their best learning.

Roxann Kriete has been involved with CRS since 1985, and was executive director from 2001 to 2011. She is the author of The Morning Meeting Book and co-author of The First Six Weeks of School.