It’s social studies time in Karen Baum’s fifth grade class, and the room is humming with activity. The class is finishing a unit on women gaining the right to vote, and the teacher has given students choices of ways to show what they learned during the unit. Some children are making a Venn diagram showing the rights of men and women during the era just before women’s suffrage. Others are creating comic strips telling of the events leading up to suffrage. Still other students are creating a magazine dedicated to the women’s movement of the time. A few children are writing letters referring to the suffrage movement from the perspective of people living during that era. The children are engaged and productive. They’re learning and enjoying their learning.

Ms. Baum’s social studies unit is an example of an Academic Choice lesson—a way of giving students a measure of teacher-guided control over what they learn or how they learn it (and sometimes both).

Academic Choice, a key Responsive Classroom strategy, is a way for elementary teachers to structure lessons and activities that empower students by providing them with options in their learning. Unlike traditional teaching methods where students passively receive information, Academic Choice involves a three-phase process: planning, working, and reflecting. When teachers use Academic Choice, they decide on the goal of the lesson or activity, then give students a list of options for what to learn and/or how to go about their learning in order to reach the defined goal.

Used well, the strategy breathes energy and a sense of purpose into children’s learning. When students have choices in their learning, they become highly engaged and productive. They’re excited about learning and sharing their knowledge. They’re likely to think more deeply and creatively, work with more persistence, and use a range of academic skills and strategies. In addition, research has generally found that children have fewer behavior problems when they have regular opportunities to make choices in their learning, a finding supported by anecdotal evidence from teachers.

Many teachers already give children choices of how or what to learn: Choose six of the following ten questions to answer. Choose a mammal to study in depth. Choose whether to write a report or make a diorama. But what sets Academic Choice apart from the choices that many teachers already offer—and what is essential to its success—is the three-phase process of planning, working, and reflecting that children go through in an Academic Choice lesson.

In the planning phase, teachers present the choices and help students select an option that will help them meet their learning goals. After the teacher introduces the activity choices, students plan what they’re going to do and sometimes how they’ll do it. In this article’s opening example, the students planned whether they were going to chronicle the events leading up to women gaining the right to vote, show what rights men and women had before women’s suffrage, or show something else they learned about the suffrage movement. Then they planned how to show their chosen content—by creating a diagram, comic strips, a magazine, or a letter.

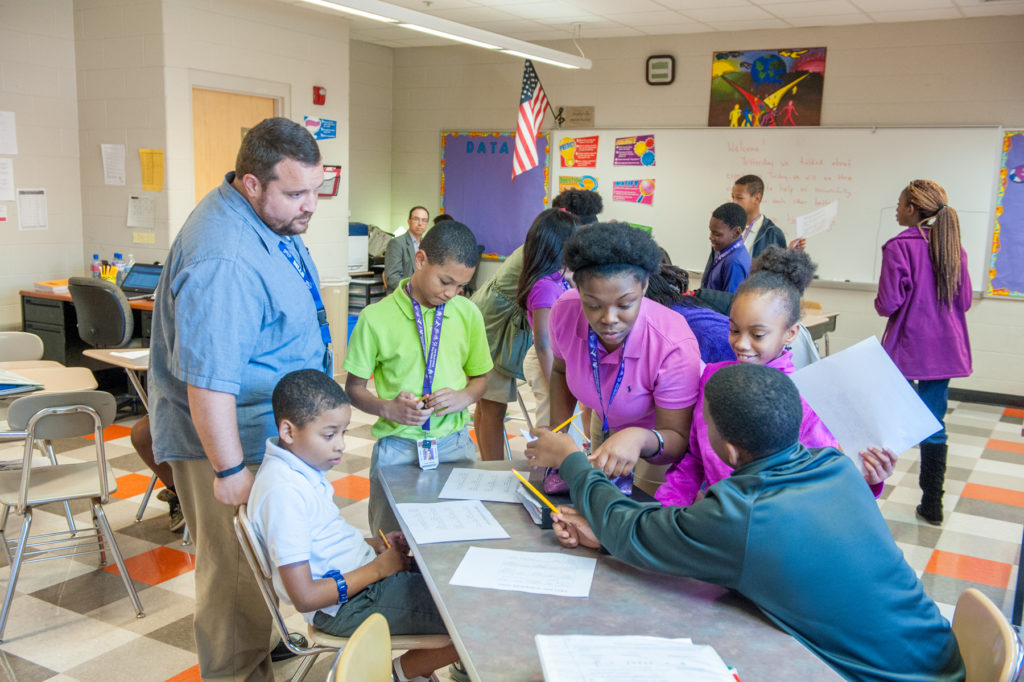

During the working phase, teachers offer support as children follow through on the choice they made during planning. The opening vignette of this article shows students in the working phase of their women’s suffrage Academic Choice lesson.

During reflecting, teachers offer prompting questions that help students think about how their work turned out, what they learned, and how their choices helped or hindered that learning. This often consists of children presenting their work to the group and discussing some aspect of their product or process. But it can also consist of a private reflection through journal writing or a self-evaluation of their work. Whatever form the reflection takes, it allows children to make sense of their concrete experiences: Why did they make the choices they made? How did their work change the way they think about a topic? What helps them learn? What went well? Why?

This cycle of planning, working, and reflecting mirrors the natural learning cycle. According to educational researchers and theorists Jean Piaget and John Dewey as well as more recent brain research, children learn most effectively when they initiate activities based on self-generated goals, work actively with concrete materials, try out ideas, solve problems, are allowed to make mistakes and correct them, and have opportunities to stop and reflect on what they’ve done. Academic Choice and its planning, working, and reflecting cycle nurture just this kind of learning in children.

“Great idea,” many teachers say, “But how do I fit Academic Choice into an already full schedule?”

The important thing to remember is that Academic Choice is not an add-on. Rather, it’s a format that can be used for many types of required lessons and activities. Academic Choice can therefore be incorporated into many portions of the day without adding to the schedule. Academic Choice can be used for three broad purposes:

In each of these examples, Academic Choice is used to structure a core lesson, not as a supplemental activity.

Academic Choice is a powerful tool for motivating students’ learning. When teachers use Academic Choice to structure lessons, children become purposeful learners who engage in an activity because they want to, not because the teacher told them to. They work with a sense of competence, autonomy, and satisfaction. This is essential to learning. This is how school should be.

For a more in-depth look at Academic Choice, including sample lesson plans, check out The Joyful Classroom.

Ready to plan your own lessons? Try out our free, downloadable resources:

A closer look at how to use Academic Choice with your students is also available in our Elementary Core Course and Elementary Advanced Course.